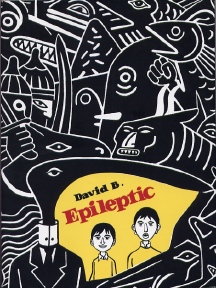

It is a strange book. Some pages are fantastic, other are awful (especially in the first half), from a comic book point of view, because it's too often the captions that carry out the narration, and too rarely the drawings. The majority of the book seems to me more like an illustrated novel than a comic book of graphic novel or as you wish to name it. I mean, the drawings alone aren't able to tell the story. They are too fixed, too rigid, there's no much dynamism in them. Dialogues are too few (even if they increase in the second half) and captions are too many. Of course David B. uses these strategies on purpose to create a story that feels as heavy as the epilepsy Jean-Christophe suffers of. But this book is just on the verge of the works that make me wonder what was the point of in making them under a graphic form instead than just a written one.

Even if I've read comics since I was a child, the residency at ACA and the last week at home have been the period in my life in which I've most thought about comics - from a theorical point of view, and not just from the perspective of a reader/author of a specific piece.

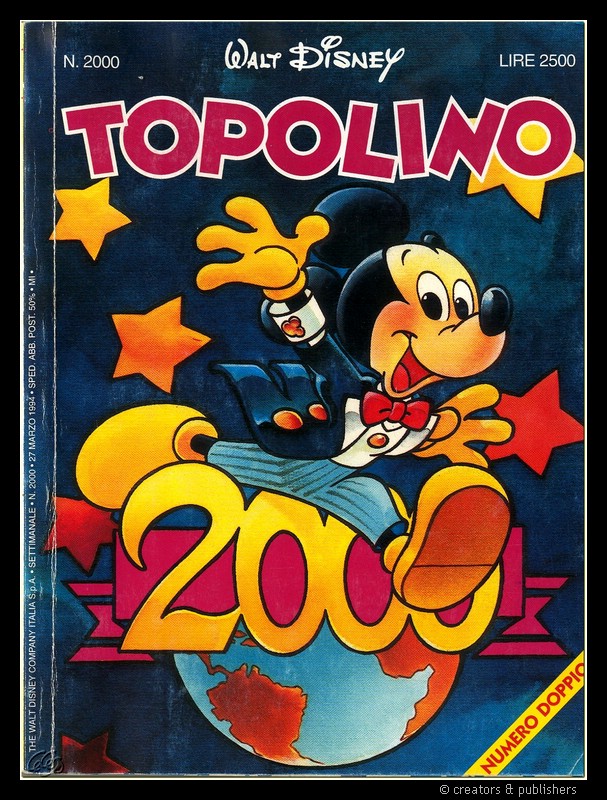

When I was a child, I regularly read three comics magazines (in Italian), plus other children's magazines which contained comics as well. The first was the Corriere dei Piccoli. It featured stories like Stefi by Grazia Nidasio and I Ronfi by Adriano Carnevale. The second was Topolino (= Mickey Mouse), which contained stories from the Disney world written and drawn by Italian artists. I suppose that almost all Italian children of the last 50 years have held a copy of Topolino sometime.

the famous n. 2000

The third was Il Giornalino, that in summer published as enclosures the comics adaptations of great classics of literature, such as Little Women, Oliver Twist, Taras Bul'ba, etc. As far as I know, this practice of publishing abridged versions of classics for children, under the form of comics (but today they'd be called graphic novels) is a specific of Italy (correct me if I'm wrong).

Aside from these magazines, as a child I read The Peanuts, Mafalda, Asterix, and I was given as a present the abridged versions of I promessi sposi by Paolo Piffarerio and of Shakespeare (Hamlet, Romeo & Juliet, The Tempest) by Gianni De Luca.

Comics, of course, were not the only texts I read. In the meantime, I have been reading also traditional, written literature. And before now, I had never seen comics and literature as opposed to each other. In my head, they were quite different. And maybe I used them in different ways, I mean that I read them in different situations and in different conditions. Now I have to confess that maybe, inconsciously, I considered comics a lighter reading than novels and plainly written works. They were for entertainment - and what a gorgeous entertainment they provided! Mangas seemed created to start fangirlism in a young girl as I was when I started reading them. Manga were made to discuss them with friends and to fall in love with handsome characters and to buy posters and photos during comic-conventions. They are able to stir deeper emotions in a reader than the average Western comics. Long stories presented an abundance of characters and each was clearly defined. In mangas you could follow psychological transitions from imperceptible details. That's why one of the funniest things I know is chatting about "what happens next" in our favourite mangas with my friends. And that's why I imagine my main comic project, Asanor, as a manga, even if it's drawn in Western style. I imagine it published in episodes during a few years and only later, eventually, collected in a few volumes. I dream about people talking about my characters and what they will and won't do and waiting for the new episode to be out in comics stores.

1 - continues...

Aside from these magazines, as a child I read The Peanuts, Mafalda, Asterix, and I was given as a present the abridged versions of I promessi sposi by Paolo Piffarerio and of Shakespeare (Hamlet, Romeo & Juliet, The Tempest) by Gianni De Luca.

These were not just comics. These were work of art and could be stared at just for the pleasure of watching something beautiful. Piffarerio (who collaborated also with the main Italian magazine of cross-word puzzles, La settimana enigmistica, illustrating rebus) was a master in drapery, while Gianni De Luca, well, he would later become one of my main influences in thinking comics.

At 12 I read - during a summer camp - my first episode of Dylan Dog (now published by Dark Horse also in the States) and continued reading it for a couple of years, until, at 14, I surrendered to a friend's entreaties and started reading Rayearth by Clamp, my first manga.

At 12 I read - during a summer camp - my first episode of Dylan Dog (now published by Dark Horse also in the States) and continued reading it for a couple of years, until, at 14, I surrendered to a friend's entreaties and started reading Rayearth by Clamp, my first manga.

1 - continues...

1 comment:

Interesting Cecilia! A record of influences and likes over the years...I'd like to try a post like this too.

Post a Comment